Valuation Adjustments: Understanding their Impact on Value

One common step in all business valuations is the “search for adjustments”–whether it be a public company with GAAP accounting or a small pass-through entity. Valuation analysts are (almost) always looking at past performance as a proxy for future value. In doing so, we need to understand the “real” earnings capacity of the company. Unfortunately, the story isn’t always so clear. Myriad factors cloud the question of “what’s real?” Nonetheless, analysts work through a process to start quantifying these changes (aka Valuation Adjustments) to earnings to realize the actual number. From there, we can work through modeling performance, risk, and ultimately value.

Why do we care? A few reasons:

- Adjustments can have a material (and sometimes downright huge) impact on value

- Adjustments can have a negative connotation – often impacting “sale-ability” in a transaction

So… we agree adjustments are important. So, how do we determine them?

Identifying Normalizing Adjustments

First, let’s classify these Adjustments. Broadly speaking, Adjustments can often be grouped into two categories:

- One-time or Non-recurring Expenses

- Discretionary/Personal Expenses

Of note, the purpose for the valuation often guides what Adjustments are reasonable. As we’ll discuss below, while some adjustments might be justified when valuing a company, the same line item might not make sense for a fractional interest in the same business.

One-time / Non-Recurring Expenses

One-time or non-recurring expenses are just what they sound like–line items that are not likely to occur again. FASB provides some helpful guidance to flesh these out. The Accounting Principle Board Opinion No. 30 defines an extraordinary item as one that is:

- Unusual in nature: the underlying event or transaction should possess a high degree of abnormality and be a type clearly unrelated to, or only incidentally related to, the ordinary and typical activities of the entity, taking into account the environment in which the entity operates

- Infrequent in occurrence: the underlying event or transaction should be a type that would not reasonably be expected to recur in the foreseeable future, taking into account the environment in which the entity operates.

How does an analyst identify these adjustments? Often, these expenses can be identified by performing year-over-year trend analysis to understand the company’s normal level of expenditure. However, on rare occasions, these expenses may be masked due to internal account classifications and can only be quantified through discussions with the Company’s management.

Typical one-time/non-recurring expenses could be the result of litigation engagements, professional/consultant fees, capital gains or losses from the sale of assets, non-cash expenses such as the built-in tax gains from those sales, and section 179 depreciation.

Discretionary Expenses

Many closely held businesses will include various discretionary/personal expenses on their financial statements. They may include above/below market owner compensation and employee salaries, ownership perks and fringe benefits, and any other expenses that are not core to business operations or otherwise likely to be incurred by a would-be acquirer.

Compensation

In pass-through entities, officer and ownership compensation is frequently normalized due to its discretionary nature. In practice, many owners pay themselves simply what the business can afford rather than the market rate for the services they perform. Ultimately, this is often what we think of as a “dividend in disguise.” The analyst should ascertain a fair market value level of compensation for the services rendered and adjust the excess. For instance, Company XYZ pays the owner $500,000 for his services annually. However, the fair market value rate of compensation for someone to perform the services of the previous owner is $150,000 – thus resulting in an adjustment of $350,000 to the Company’s financial statements to reflect the true economic benefit stream available to the acquirer.

Additionally, payroll salaries for “ghost” employees—employees who are on the Company’s payroll but do not actively participate in the business’s operations—may exist and need to be adjusted out. Often, these are family members who receive some level of compensation from the company without employment capacity.

Non-Core Expenses: Sometimes, a business incurs expenses that are not central to operations. For example, a recent client had been funding startup and development costs for a sister company with common ownership. These expenses are not related to the company’s operations and, as such, are a frequent target for adjustment.

Fringe/Ownership Perks: In addition to officer compensation, many business owners will often expense personal items to the company. Putting aside the ramifications of doing so, simply put, these are not operational expenses and are targets for adjustment. Typical examples might include personal car expenses, travel and meal expenses, certain professional fees, and other expenses that benefit the owners/officers and deviate from the normal business operating costs.

Illustrating Normalizing Adjustments

Analysts must adjust a business’s financial statements or income tax returns to most accurately derive an income benefit stream that can be capitalized. Depending on the company, its historical financial statements and “adjusted/normalized” financial statements can diverge significantly, thus resulting in a significant difference in the overall value. Also, normalizing the financial statements allows the analyst to compare similar companies and industry averages and make meaningful projections and forecasts.

Valuation Adjustments: An Example

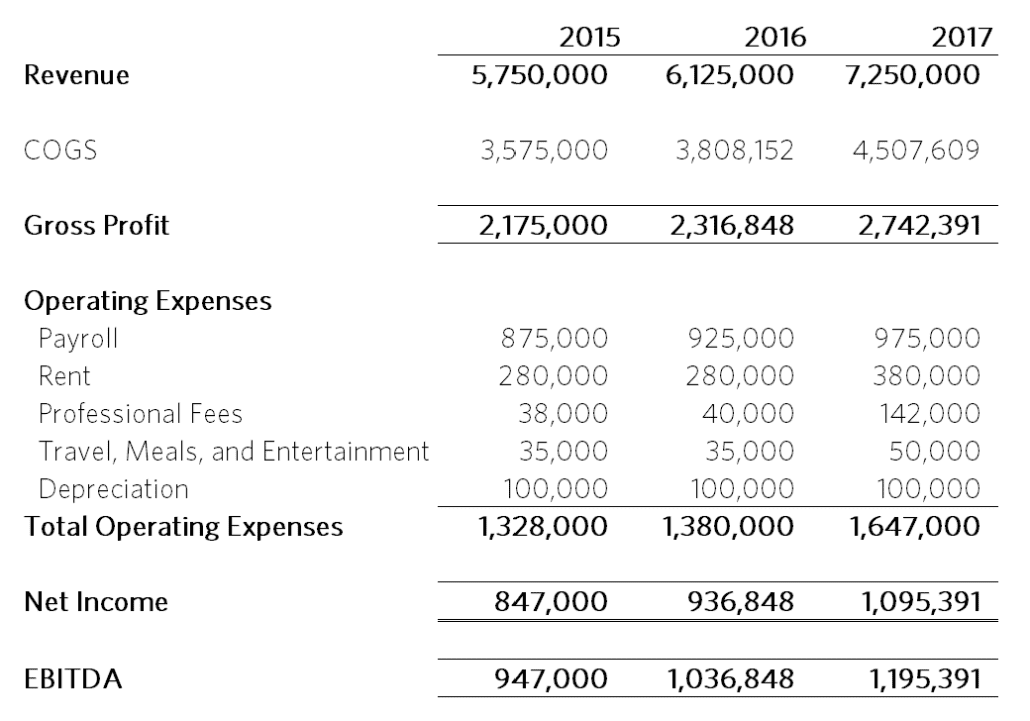

Below are the historical income statements for Company XYZ. Note that the Company is a pass-through entity and does not pay taxes at the corporate level.

The Fact Pattern

Understanding the following fact pattern, we can identify several normalizing adjustments:

- The Company has two owners/officers who receive equal compensation. Bob is the majority owner with 80% ownership, and Mike is a minority owner with 20% non-voting ownership. The market salary rate for both officers’ services would be approximately $150,000 each.

- The Company had a one-time settlement fee of $100,000 for a lawsuit in early 2017

- The Company prepaid half of the FY18 rent expense in FY17, equal to $100,000

- Bob opened a new Hawaii office in 2017 at a yearly cost of $80,000. However, there really is no business there, and it is more of a perk than an office.

- Bob and Mike took several vacations this year and booked their personal travel and meals in meals and entertainment. Meals and entertainment with clients typically amount to $35,000 on average. FY17 exceeds the average by $15,000.

- Bob employs his sister at $57,000 per year – however, this is a “no-show” job.

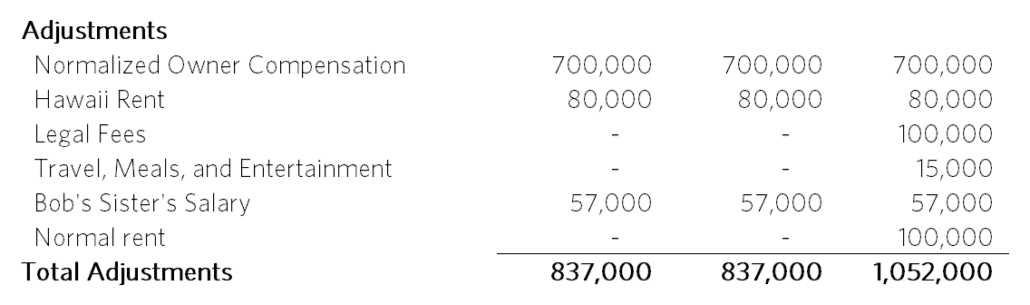

We account for these discretionary/one-time expenses by normalizing the above items below:

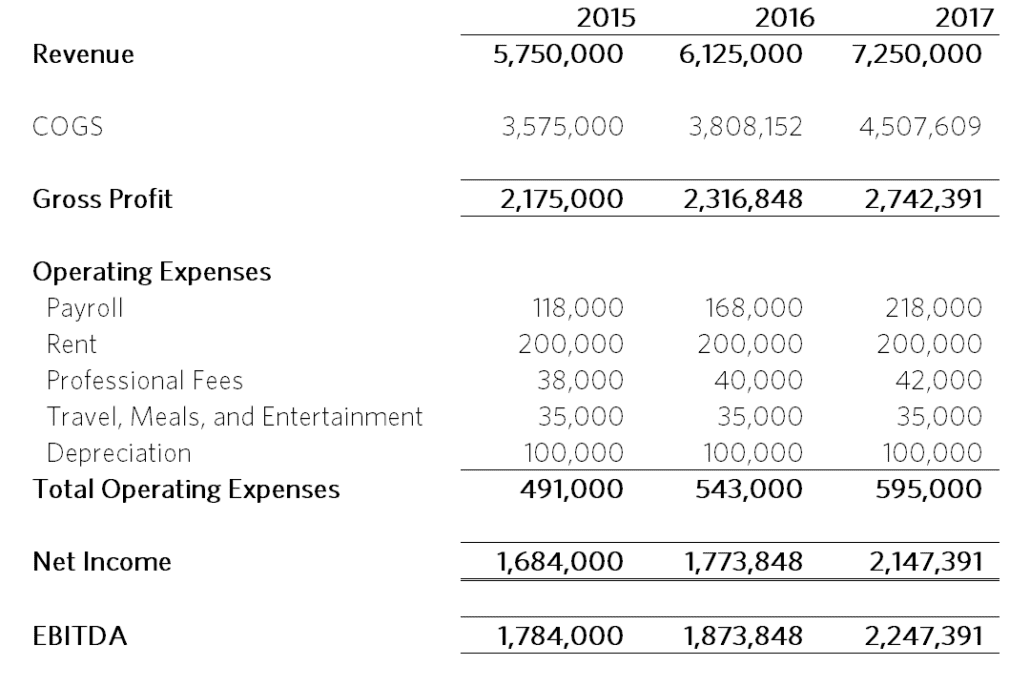

Once the analyst has normalized the Company’s income statement, the resultant “adjusted” income statement reflects the true economic benefit stream an acquirer can expect to inherit. See below:

Normalizing the financial statements results in adjusted earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization expense (“EBITDA”) of $2,247,391—an increase of 88.0% on the most current year’s income benefit stream!

Adjustments’ Impact on Value

Below, we present a simplified market approach analysis that capitalizes on the benefit stream (EBITDA) in the most recent year by comparing similar companies that have recently been transacted.

With the guideline companies analyzed, the market approach implies an EBITDA multiple of 5.0x, resulting in a value of $11,236,957. If we had not taken the time to normalize the company’s EBITDA, we could have significantly undervalued it by $5,260,000, further emphasizing the necessity to account for any one-time/non-recurring or discretionary expenditures.

What About Saleability?

As companies get larger, they often adopt better governance practices and comply with GAAP requirements. Not so with smaller entities. Oftentimes, owners will treat a company as their own “piggy bank”- running a variety of expenses through the business. (True story: we once saw a six-figure racehorse expensed to a fire sprinkler company!) While we can (and do) certainly make adjustments for these sorts of truly non-business-related items, the bigger issue is that they create a sense of doubt for a buyer. After all, if the company is so cavalier with their financial reporting as to expense a racehorse, what other shenanigans are going on? In our experience, buyers tend to walk away from situations where adjustments are either very aggressive or where they are a material portion of earnings.

The bottom line for owners is to clean up their financials well in advance of an exit! It’s better not to rely on aggressive adjustments to try to substantiate your purchase price.

Valuation Adjustments: Final Take-Aways

Every valuation assignment involves the search for adjustments. Our goal is to understand the company’s real, ongoing cash flow performance, which flows through to value. That said, unlike our vignette, the process is far from straightforward. Special attention needs to be paid to getting the details right with adjustments. As a business owner, it might be even more important to consider how cleaning up financials will correlate to value and saleability as you get close to an exit!

As a business owner, you know your business. To sell it successfully, you need to understand the numbers, too. A professional business valuation ensures that you get an accurate assessment of your company’s current worth. Since 2003, Quantive has performed over 3,000 business valuations. Contact our valuation specialists for a no-cost consultation today.