Beware of Valuation Rules of Thumb

Valuation Rules of Thumb are a common way to estimate the value of a business. They are easy to comprehend and seemingly broadly apply. But reader beware: at best, they represent an average. And in real life, there’s often no such thing as “average.”

Bear with me here on a bit of history: Back in the 1940’s, the US Army Air Force had a problem: their pilots kept putting aircraft in the dirt. As you can imagine, for a military branch whose main objective was flying, crashing was clearly an alarming trend. The Air Force undertook a massive study measuring every nook and cranny of over 4,500 pilots. Eventually, they determined that the root cause of crashes was cockpits and controls that were not the right size for pilots. As propeller planes became jets and became faster and more powerful, the small inefficiencies in cockpit layouts became the stuff of life or death. So, how to address this problem?

They decided to average.

Fortunately, a nerdy young Lieutenant- Gilbert Daniels- took umbrage at this averaging. As the Air Force pushed manufacturers to develop a cockpit for the average pilot using 10 key dimensions, Daniels crunched the numbers. The expectation was that by designing to the average, that most pilots would be well within the specs on these 10 dimensions. So, out of 4,500 pilots, how many were average? Not a single one. In the real world, the average is a statistical lie.

Valuation Rules of Thumb are averages. They assume that every company exposed to that rule is pretty much the same. They do not take into account how a particular company may stack up to peers – and hence, can be a very dangerous method to rely on for anything other than reminiscing.

A Rule of Thumb Example

Suppose for a moment that you are considering buying a company and looking at two potential companies. For argument’s sake, we’ll call it a dental practice. Here are two commonly used “Rules of Thumb” for the dental industry:

- 65% of Gross Revenues

- 2x Net Income

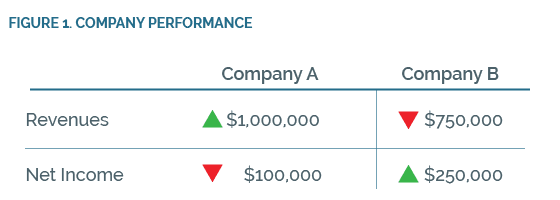

So, let’s apply those to the two hypothetical companies below.

Company A has significantly higher top-line revenues than Company B. This could be for myriad reasons- better location, longer time in business, or perhaps just a friendlier staff. That being said, despite lower revenues, Company B has earnings that are 2.5x higher than A. Perhaps they have better procedures, their workforce is better trained, or they have more efficient purchasing procedures. Whatever the case, Company B produced significantly more earnings per dollar of revenue than A.

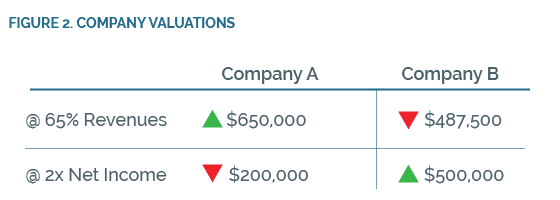

So what are they worth? Applying the above rules of thumb results in the below valuations:

Two companies, four different values, and none even hardly close to one another. So, how do you reconcile those numbers? Should there be any situation in which a buyer would pay $650k for A and still consider B less valuable? Maybe. But there would have to be some serious problems with B (example: B’s profits are inflated by one-time insurance proceeds).

Which would you pay more for? What is the right number here? Simply using a rule of thumb, we’d never know.

That Pesky Bell Curve

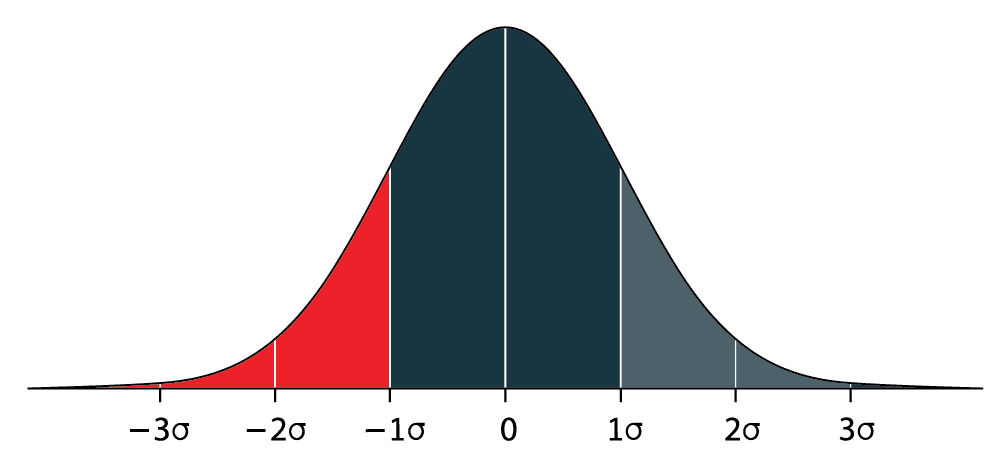

I’m forever going on and on about how valuation lies along a spectrum. For any given industry or type of company, there is a potential range of value. Some companies are going to be on the low end of that spectrum, a big pile will lump in the middle, and then a few are going to be rockstars that are way more valuable than their peers. This is what value looks like in the real world:

The bell curve shows us that, for some companies, those rules may (or still may not!) be accurate, but not many are going to be exactly right. That’s because every single company is unique. What differentiates one company from the next? The list is endless, but factors might include:

- Margins

- Intellectual property

- Location

- Relative strengths/weaknesses of the assembled workforce

- Growth Rate

- Et cetera et cetera

Company B above may have all sorts of structural problems that are going to impair value and bring it way down below the middle of the bell curve. Likewise, Company A might have a great recurring revenue stream with a low breakage rate that yields a higher overall valuation.

Conclusions

Simply relying on rules of thumb is a risky proposition. If you find yourself sitting around wondering about your valuation, then fire away. But if you actually need to know your value – you know, for something like an actual sale, a buy-sell agreement, an acquisition, or a divorce matter- then it’s probably time to talk about an actual valuation by an accredited professional.